Rethinking the Quantum Business Model: Erik Hosler on Innovation Through Affordability

For most emerging technologies, the story begins with discovery and ends with adoption. Quantum computing reverses that order. Its breakthroughs often appear in research papers years before they can be made practical, yet its survival depends on proving it can be sustained as a business. Erik Hosler, a semiconductor systems strategist and quantum process economics specialist, highlights how affordability has become the most valid form of innovation in the race to commercialize quantum computing. His view reframes the field, placing value and viability alongside speed and performance as the core measures of progress.

Quantum engineering has reached a stage where technical advancement alone no longer defines success. Each new generation of hardware pushes the boundaries of precision, but the real competition lies in cost control, reliability, and manufacturability. Investors, governments, and industries watching the field are not asking whether quantum computers can be made to work. They are asking how they can be applied. They are asking whether they can afford to. The future of quantum computing can be written not only by scientists but by those who can balance discovery with discipline.

The Price of Potential

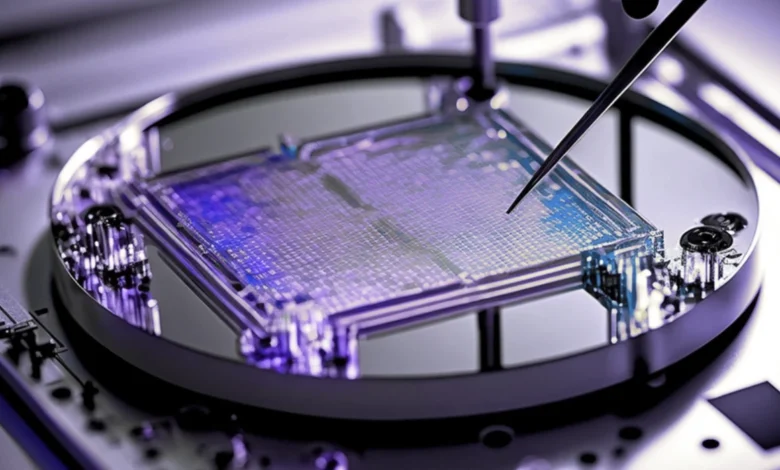

Building a quantum computer remains one of the most complex engineering tasks in existence. The machines require vacuum chambers, cryogenic systems, and layers of materials precision-engineered to atomic tolerances. The expense of creating even a single functioning qubit runs into thousands of dollars when accounting for fabrication, testing, and environmental control.

Early-stage research could rely on academic funding, but scaling to commercially viable systems demands repeatable processes that lower cost without sacrificing coherence. This tension defines the new frontier of innovation. The companies leading the field must now focus as much on economic efficiency as on technical possibility.

The central question is simple. Can quantum computing become a business that sustains itself without perpetual subsidy? The answer may depend on how efficiently the technology can leverage existing manufacturing systems and distribute costs through a modular design.

Borrowing from the Silicon Model

The semiconductor industry provides both a model and a warning. Its success grew from a feedback loop between design optimization and cost reduction. Each new node generation increased performance while reducing unit cost, creating a virtuous cycle that expanded access and investment. Quantum technology has not yet achieved such self-reinforcement.

To do so, it must integrate with existing manufacturing infrastructure rather than rebuild it. Semiconductor facilities already possess the precision equipment, environmental control, and patterning expertise needed for quantum fabrication. Repurposing these capabilities can reduce capital expenditure and shorten production timelines. The challenge lies in designing architectures that meet these constraints without compromising functionality.

The Economics of Noise

Every qubit is both a financial and a physical investment. Noise reduction, error correction, and calibration each add cost. The ratio between usable and physical qubits represents both a scientific and economic challenge. If thousands of physical qubits are required to produce one stable logical qubit, production costs rise exponentially.

Companies pursuing photon-based architectures see an opportunity to escape this curve. Photonic qubits, fabricated with existing semiconductor processes, can reduce dependency on exotic materials and extreme temperatures. This compatibility with standard manufacturing lowers entry costs while allowing scalability through established industrial supply chains.

The Practical Imperative

As the race to build larger systems accelerates, the focus on cost becomes unavoidable. The most elegant design means little if it cannot be reproduced within realistic budgets. Erik Hosler says, “We need to build a quantum computer that doesn’t break the fab and doesn’t break the bank.”

His statement captures the challenge facing the industry as it moves from prototype to production. The phrase combines technical and economic truths. “Fab” represents the limits of manufacturing feasibility, while “bank” reflects the limits of financial sustainability. His insight turns affordability into a performance metric, placing it alongside speed, stability, and accuracy as a measure of maturity.

The idea extends beyond cost control. It implies a structural shift in how innovation is measured. Building responsibly becomes part of building intelligently. The quantum companies that succeed can be those that treat fiscal efficiency as a feature, not an afterthought.

Investment Meets Infrastructure

The economics of quantum computing depend as much on trust as on technology. Investors require evidence that the field can sustain predictable growth. That confidence comes not from abstract projections but from factories capable of consistent output. Each successful fabrication cycle proves that quantum computing is not only possible but repeatable.

This shift toward industrial validation alters how funding is allocated. Public and private investment now favors companies that demonstrate operational discipline. Those with clear cost models and scalable infrastructure attract the capital needed to accelerate development. The conversation has developed from “What can quantum do?” to “Who can build it most efficiently?”

A New Metric for Innovation

In the past, innovation was measured by novelty. The most advanced device was the one that achieved something never done before. Today, innovation is increasingly measured by accessibility. A breakthrough is only meaningful if it can reach beyond a laboratory or prototype.

Quantum computing’s long-term influence may depend on affordability in both construction and operation. When cost falls, adoption rises. When adoption increases, so does the incentive to refine and improve the process. It is how industries mature, turning experiments into economies.

In this model, progress is not only technological but social. A system that costs less to build can serve more institutions, accelerate research, and foster new applications in medicine, logistics, and sustainability. The economics of access become the new ethics of innovation.

Building What Can Endure

Quantum computing began as a race to prove feasibility. It now enters a phase defined by responsibility. The path forward depends on maintaining a balance between ambition and affordability. The machines that endure can be those designed with both precision and prudence.

Affordability does not dilute innovation. It strengthens it. Each decision to simplify a process, reuse a facility, or reduce waste contributes to long-term progress. Cost awareness becomes a creative act, shaping technologies that can sustain their own development and growth.

The companies that master this mindset may define the future of quantum computing. They may not only build powerful machines but also establish the frameworks that make those machines viable. In doing so, they may demonstrate that innovation measured by impact must also be measured by endurance.